Biologically inspired design derived from the process of learning from nature has created an entire field that aims to integrate design approaches influenced by nature and living systems. From this stems biomimetics, an interdisciplinary design method that strives to emulate how organisms tackle fundamental problems in engineering. Bridging the gap between biological systems and human technology has incentivized a bottom-up approach for biologically inspired design that focuses on the principles of biomimicry and biomimetics.

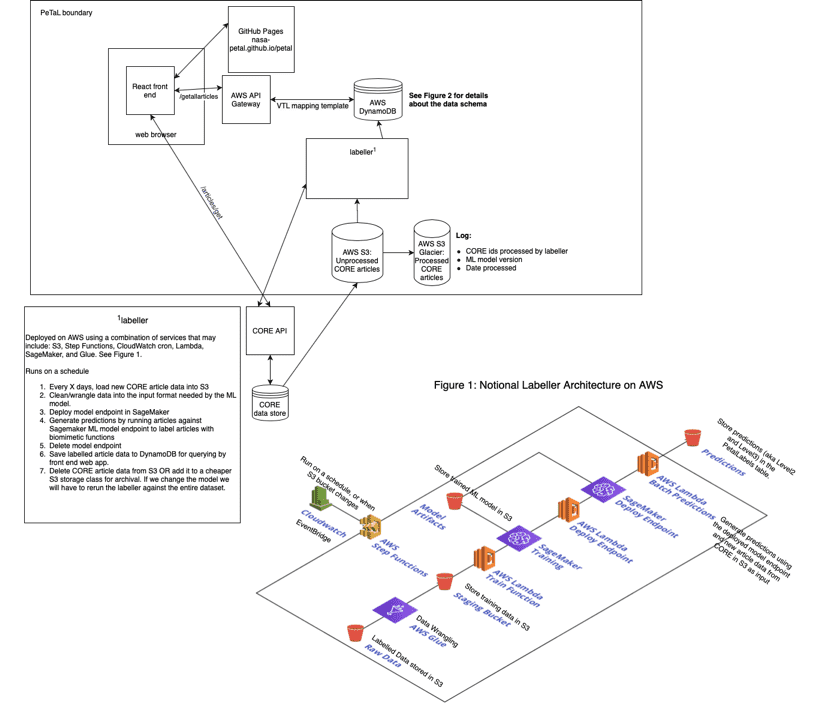

The Periodic Table of Life (PeTaL) is an open-source, artificial intelligence (AI) tool that aids in the design and integration of aerospace and human systems based upon biomimetic and bionic processes. It aims to streamline the process between steps in the biologically inspired design process and accessibly present solutions to biologists and engineers through relevant biological literature and data relating to functional living systems. PeTaL specifically leverages the latest advancements in machine learning and natural language processing (NLP) to develop an AI-powered system that can learn and suggest solutions to biomimetic design inquiries. It is built for engineers and designers who intend to solve their structural problems with nature’s solutions and for biologists looking to apply their research to engineering.

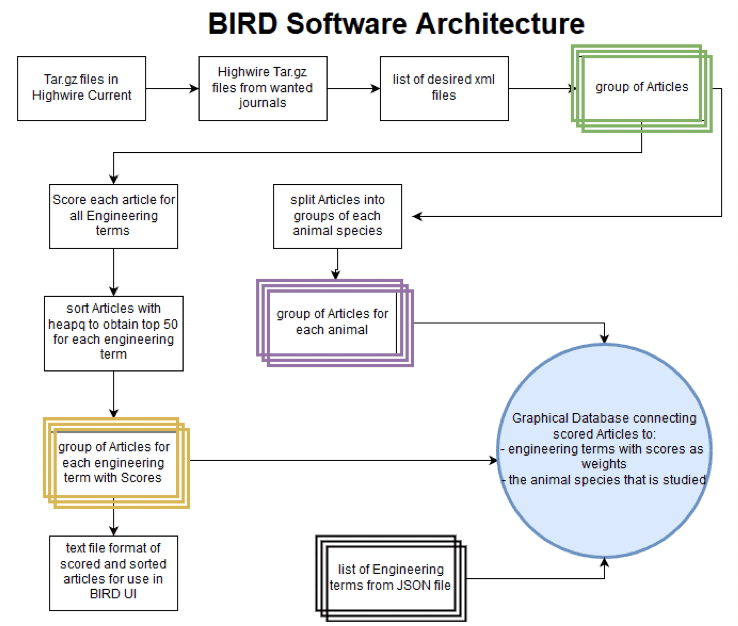

Recently, a goal was set to build a new minimum viable product (MVP) application, based on a dataset of over 1,400 peer-reviewed and labeled biological journal articles and a redesign of the existing web application, Biology Inspired Nature Design, or BIRD. Through a specialized search engine, BIRD “translates” common engineering challenges to biological terminology. A user-friendly PeTaL web interface will let users interact with an NLP-based labeling tool that classifies papers by relevant biological functions and a dynamic catalogue of those scientific papers. A RESTful (representational state transfer) API is also being integrated for internal and external development use.

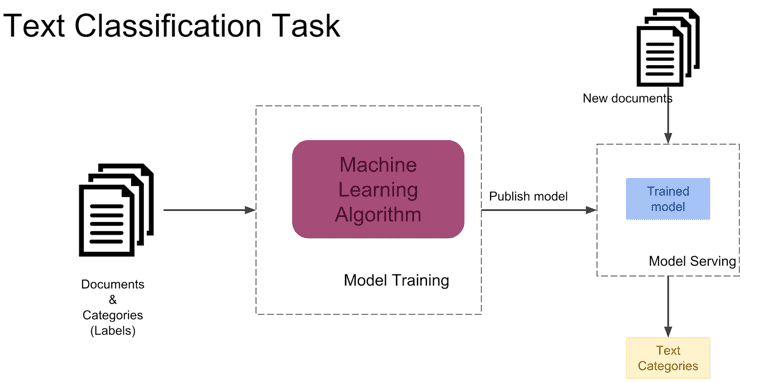

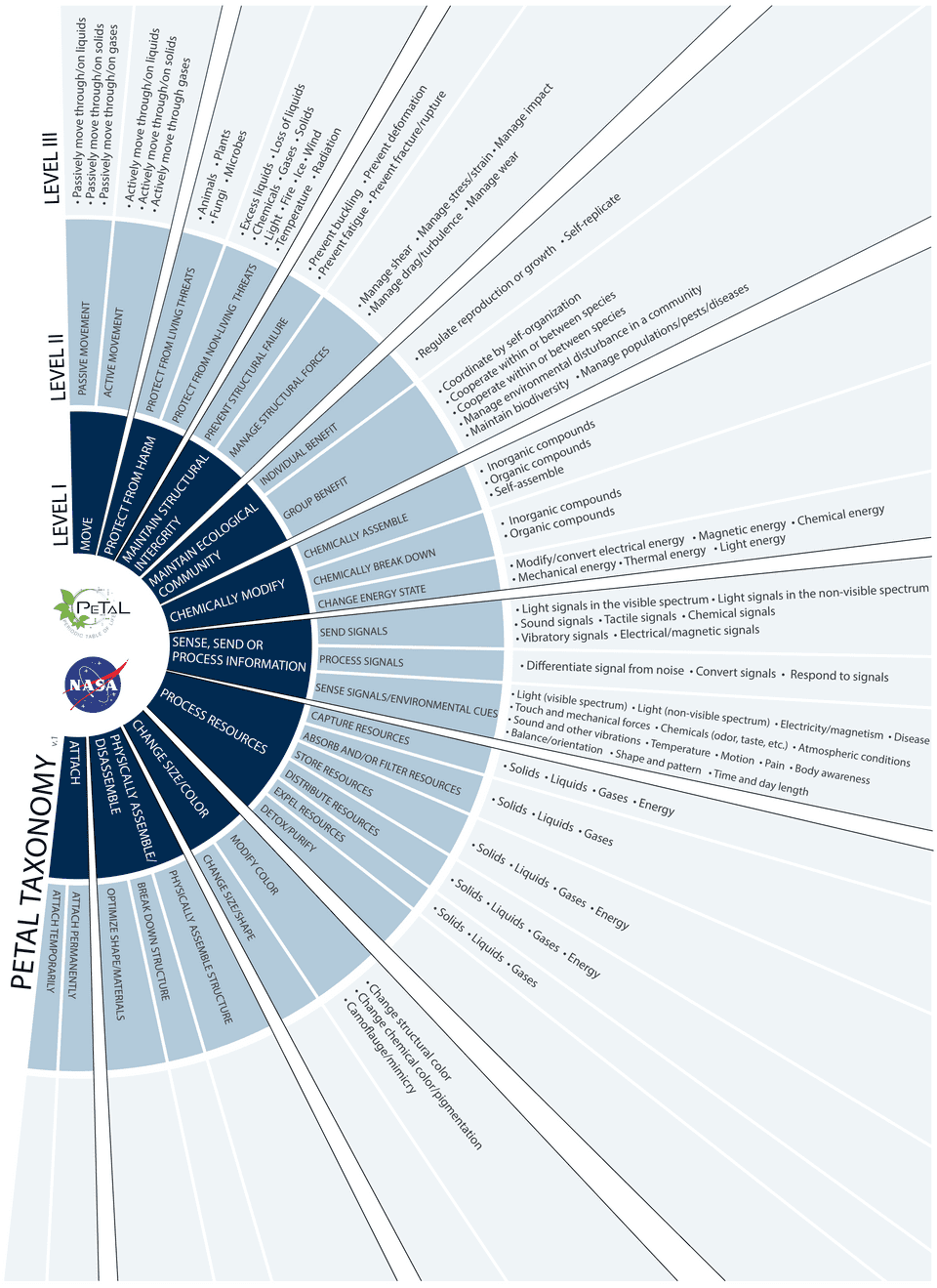

The article labeling tool uses text classification and NLP models to generate function labels based on a unique biological taxonomy curated by the PeTaL development team. Our final model will be used to classify thousands of relevant publications and label them with one or more biological functions catered to the end user’s searches. Each function label has corresponding subgroup functions, split up into Level I, II, and III functions. For example, a paper about how penguins retain their heat could be classified with the “Protect from temperature” Level III function label. Therefore, it would also fall under the “Protect from non-living threats” Level II function label, and “Protect from harm” Level I function label. (see Fig. 3) For the MVP, publications will be labeled with Level I function labels from the PeTaL taxonomy. Once papers are classified, the PeTaL interface will allow users to search for functions that solve specific engineering problems.

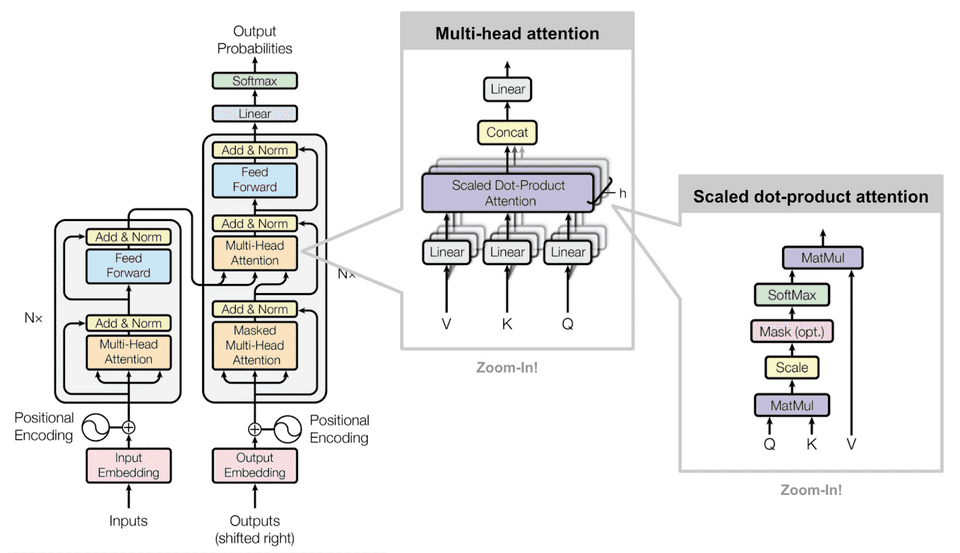

The model driving our labeling tool is built using Transformers, a unique bidirectional neural network that is able to solve large sequence-to-sequence NLP problems. Transformers rely on self-attention, which allows models to better derive context and semantic meaning of words and phrases through the way it computes similarity. As the transformer model processes each sentence, the self-attention layer mechanisms operate to have each word analyze its surrounding words to see how a specific word relates to the rest of the sentence and its contextual meaning.

Let’s look at a specific example: in the sentence “The dog jumped over the fence because it was being chased”, what does the word “it” refer to? By analyzing the sentence’s subject and predicate structure, we can derive that “it” is referring to the “dog”. If we were to keep adding more phrases to this sentence, it could get more complicated and difficult to understand the underlying context. However, with the Transformer’s ability to “focus” on certain areas of a sentence through attention mechanisms, it is able to understand context of all surrounding words.

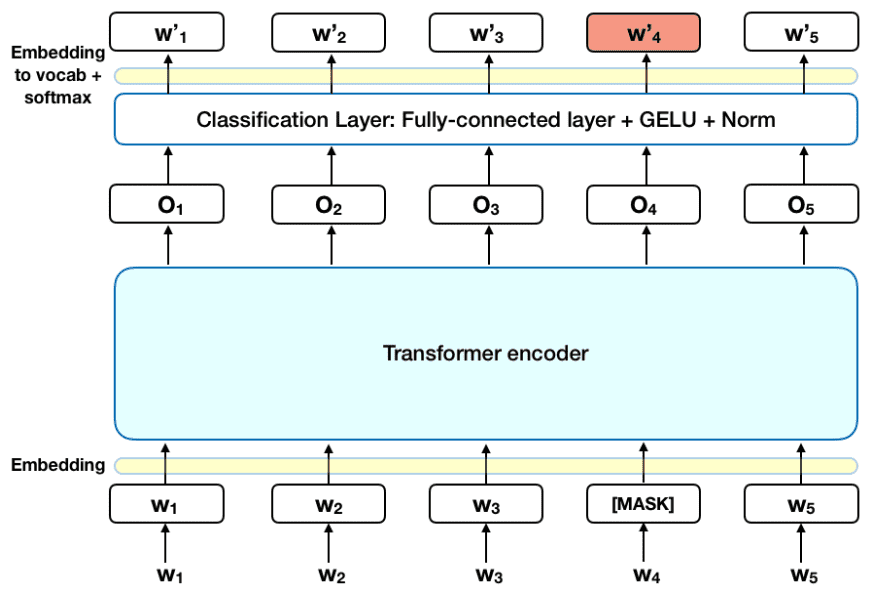

Through transfer learning, where a trained model or neural network can be applied to another task or domain, we created a Transformers-based labeler model fine-tuned using the BERT model architecture. BERT specifically allows for better understanding of contextual meaning within the journal articles, since it uses a masked language model through semi-supervised sequence learning to derive context and semantics from surrounding words.

BERT uses masking to hide a few words in a phrase or sentence and forces the model to predict the masked words based on the surrounding, non-masked words within the sequence; comparable to a fill-in-the-blank process. This process means the BERT model cannot “cheat” by looking at the following word, thereby learning nothing. Following this, BERT uses another training technique, called next sentence prediction, to predict an entire sentence just by using its preceding sentence. Pretrained on a large corpus of unlabeled text consisting of over 3.2 billion words from BookCorpus and Wikipedia combined, BERT reduced our project’s dependence on a larger training dataset. For further multi-label text classification, the pretrained BERT model was altered specifically for this task with the use of an additional sequence classification layer.

An important piece of Transformers, BERT, and other NLP models is the tokenizer. A tokenizer uses lexical analysis to convert a stream of text into token sequences. This process is necessary to develop semantic units for processing into a pattern that a machine or complier can understand for processing. It splits sentences and phrases into smaller units which are then matched up to distinguishing numerical identifiers. BERT tackles tokenization through the WordPiece algorithm, by using sub-words to break down word structures into building blocks for other terms within a corpus (i.e. burning = bu + rn + ing –> tu + rn + ing = turning).

Common words like those listed above can be easily broken down and built back up. However, more complex terms, like scientific and biological words, are usually not present in a model’s default token library. This poses an issue for the PeTaL labeler, because the papers used to train our model with are filled with scientific terminology.

Initially, we added our own vocabulary into BERT’s tokenizer model, but this modified the embeddings on which BERT was originally trained and risked a reduction of its performance and accuracy. After thorough research, we came across SciBERT, a BERT model trained on scientific text, developed by the Allen Institute of AI. This model has its own vocabulary for the tokenizer catered to match the training corpus of Semantic Scholar papers. We are in the process of refining our model to the SciBERT architecture and vocabulary through transfer learning.

One of the biggest challenges in developing the labeling tool has been the lack of annotated training data, resulting in low accuracy rates. Our current methods include scraping multiple journal servers for articles and abstracts that have been prelabeled by our team of biologists. We are also using Amazon Mechanical Turk to crowdsource labeled data from biomimicry and biology professionals across the world.

Through our development of a cloud infrastructure, the labeling model will be implemented within the PeTaL architecture through AWS Sagemaker and the PeTaL API. This will allow the model to streamline communication between the web interface and dynamic database of publications.

The PeTaL team is continuing to develop an MVP with a growing team of NASA engineers, interns, biologists, and other open-source contributors, as we envision a streamlined product that makes biologically inspired design tools accessible and understandable to a wider scientific audience beyond experts in biomimicry. We are seeking engineers and researchers who may be potential users of PeTaL to test our product in the coming months. Please reach out to us if you are interested.

— Shruti Janardhanan

References

Beltagy, I., Lo, K., & Cohan, A. (2019). SciBERT: A Pretrained Language Model for Scientific Text. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), 3615–3620. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/D19-1371

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2019). BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. ArXiv:1810.04805 [Cs]. http://arxiv.org/abs/1810.04805

Ghati, G. (2020, May 13). Head Pruning in Transformer models ! Medium. https://towardsdatascience.com/head-pruning-in-transformer-models-ec222ca9ece7

Horev, R. (2018, November 17). BERT Explained: State of the art language model for NLP. Medium. https://towardsdatascience.com/bert-explained-state-of-the-art-language-model-for-nlp-f8b21a9b6270

PeTaL. (n.d.). Glenn Research Center | NASA. Retrieved April 29, 2021, from https://www1.grc.nasa.gov/research-and-engineering/vine/petal/

Shyam, V., Friend, L., Whiteaker, B., Bense, N., Dowdall, J., Boktor, B., Johny, M., Reyes, I., Naser, A., Sakhamuri, N., Kravets, V., Calvin, A., Gabus, K., Goodman, D., Schilling, H., Robinson, C., Reid II, R. O., & Unsworth, C. (2019). PeTaL (Periodic Table of Life) and Physiomimetics. Designs, 3(3), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs3030043

Text Classification | Katacoda. (n.d.). O’Reilly KataKoda. Retrieved April 29, 2021, from /basiafusinska/courses/nlp-with-python/text-classification

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, L., & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention Is All You Need. ArXiv:1706.03762 [Cs]. http://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762

Wu, Y., Schuster, M., Chen, Z., Le, Q. V., Norouzi, M., Macherey, W., Krikun, M., Cao, Y., Gao, Q., Macherey, K., Klingner, J., Shah, A., Johnson, M., Liu, X., Kaiser, Ł., Gouws, S., Kato, Y., Kudo, T., Kazawa, H., … Dean, J. (2016). Google’s Neural Machine Translation System: Bridging the Gap between Human and Machine Translation. ArXiv:1609.08144 [Cs]. http://arxiv.org/abs/1609.08144